- Home

- Better Memory

- Memory Systems

- Memory Association

Visualization & Association

Most people know that memorizing by repetition (learning by "rote") does not work well.

They just don't know how else to memorize, other than using a few memory tricks that are useful in special situations.

However, there are some memory techniques that really do work for any type of memorization task. I refer to these methods as memory systems.

These systems can be used to memorize just about anything, including:

Definitions, language vocabulary, science terms, math formulas, Bible verses, news articles, theories, history facts, product information, procedures, art & music, computer terms.

The memory systems include the Keyword Method, Link Method, Peg Method, Journey or Loci Method, Face-Name Method, and Phonetic Number Method.

Some of these techniques are hundreds of years old. In recent years they've been popularized in books by memory guru Harry Lorayne and many others.

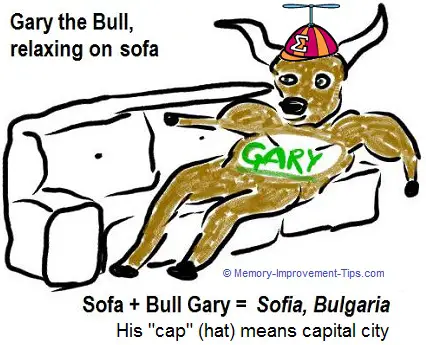

This is Gary the Bull.

Below, I explain how Gary helps me remember that Sofia is the capital of Bulgaria.

The central technique at the core of most of the memory systems is Visualization & Association (V&A for short) plus the substitute word technique. This is the first memory skill you'll want to master as you learn to use the memory systems effectively.

How Visualization & Association Works

The three basic steps of the V&A technique are:

- Use "substitute words" to break down complex concepts.

- Use your imagination to create vivid mental images of the ideas.

- Mentally associate the visual images you created to each other.

There are several advanced systems (such as the peg methods), but the three steps above are how you form the basic mental links.

Step #1: Use Substitute Words

Associating new information with information your already know is the key to really memorizing something. To "associate" means to create a mental connection, and for most people the best way to create this connection is through visualization. There are scientific reasons for this.

For example, most people have a hard time describing the shapes of different countries. Could you draw an outline of Columbia from memory? But almost everyone can roughly visualize Italy's outline - it is in the shape of a boot (a visual cue).

For example, most people have a hard time describing the shapes of different countries. Could you draw an outline of Columbia from memory? But almost everyone can roughly visualize Italy's outline - it is in the shape of a boot (a visual cue).

So if you can associate new information with an image you can easily visualize, that new information will become much more firmly locked in your memory.

But how do you associate something abstract like a math formula to an image? Or what about a city name, like "Hobart" or "Cincinnati"? Or foreign language words like the Russian word for "hello", ![]() ?

?

The secret is to use substitute words. You can convert any concept, word, symbol, or other information to something familiar by breaking down the sounds that make up the word and then thinking of memorable images of the parts.

For example, consider the city name "Hobart" (a city in Tasmania). The word Hobart is not a regular word like "apple" or "car" that can be easily visualized. So to convert Hobart to visual form, break it down phonetically (by sound) to concrete words.

The words that come to my mind when I say the word "Hobart" are "hobo" plus "art" (hobo-art = Hobart). I can picture in my mind a hobo, which is a kind of travelling vagrant. I can also picture art (I see a painter's easel and canvas).

If the word you need to remember is already something you can visualize (like "apple"), you can skip Step 1 and go straight to Step 2.

Step #2: Create Vivid Mental Images

To build strong mental connections to the new information, the images must be very memorable, because ordinary things are too forgettable.

To build strong mental connections to the new information, the images must be very memorable, because ordinary things are too forgettable.

The silly, the impossible, and the outrageous are easy to remember. For example, do you remember what you had for dinner on Thursday three weeks ago?

Probably not. But most people would remember their first day of high school or college, or their first date, or their first day at their new job, because these were memorable events.

When something stands out, we remember it. So your mental images must be the same way.

Here are a few guidelines for making images memorable:

Exaggerate the proportion - make the item gigantic in your mind.

Exaggerate the number - think of millions of the item.

Get action into the picture.

Use substitution to replace one item with another.

In the example with the city name Hobart, I should choose one or more of those rules to help make the images memorable. One obvious one would be introducing the action of the hobo painting a picture on the canvas.

For even more ideas on how to memorable pictures, see my 6 Tips to Create Effective Mental Images page.

While probably unusual, that mental image may need something more to make it memorable. So perhaps I imagine a gigantic hobo crouched down and painting on a very tiny canvas.

Try to picture that in your mind. You'll see how this all pulls together in Step #3 (below).

Step #3: Associate the Images Together

In Steps #1 and #2 you think of substitute words for any complex words and then create vivid mental images of those words. Step #3 is where you start connecting the information together.

In Steps #1 and #2 you think of substitute words for any complex words and then create vivid mental images of those words. Step #3 is where you start connecting the information together.

In my Hobart example, there was only one piece of information - the name of the city. However, that is a trivial example, because usually you need to remember many pieces of information and how they all relate to each other.

For instance, you might need to remember that Hobart is a city in Tasmania, and that it is the capital there.

For each of the separate facts you want to remember, you first go through Steps #1 and #2. Once you have images in mind for all the facts, you connect them (link them) using Step #3.

These connections are almost always formed by thinking of some kind of action that puts the images together.

Let me extend the example. I already have my "hobo+art" imagery to remind me of the name of the city of Hobart. Now I want to remember that Hobart is the capital of Tasmania.

For "Tasmania", the substitute word that comes to my mind is the cartoon Tasmanian Devil (which you may remember from Saturday morning kids shows). For "capital", I picture in my mind a silly-looking cap (hat) with a tall propeller on top.

Here's how I form my association: First, for Tasmania, I imagine the Tasmanian Devil; and he is putting the silly-looking propeller cap on his head. So when someone asks me about Tasmania, an image of that cap automatically appears in my mind.

Now I need a link between "cap" and "Hobart" to remind me that Hobart is the capital. So I imagine my gigantic hobo smearing paint on a canvas using a cap or hat of his own. (The hobo's cap does not need to match the Tasmanian Devil's cap for the link to work.) Then I run the images through my mind a few times to make sure I can clearly visualize them.

It's that simple. When someone asks me the question, "What is the capital of Tasmania?", the image of the Tasmanian Devil cartoon figure pops into my head; that makes me think of the image of the Tasmanian Devil putting on his silly-looking cap; the cap itself makes me think of the image of the hobo painting a picture using his cap. The image of the hobo creating art with his cap tells me the capital must be hobo + art, which is the name "Hobart"!

I encourage you to try this exercise yourself. You will be amazed at how easy it is to form the mental pictures and link them. And the more you practice, the easier it gets (like with any other skill).

Example #2 - Memorize the Capital of Bulgaria

Here is a simple example I created that uses "substitute word" plus visualization to memorize that the capital of Bulgaria is the city Sofia. I've pulled the three steps explained above into one image that shows how this technique works.

Neither "Bulgaria" nor "Sofia" are easy to imagine as objects. So I've used the substitute word technique to think of objects that are easy to visualize.

The sound of the word Sofia reminds me of "sofa" (a couch). Bulgaria sounds to me like "bull + Gary".

You can also include actions when using this technique. Movement can help make an image more memorable:

Remember: Choose subsitute words that you find memorable. For instance, to you the phrases "so free", "sew fee", etc. might be easier to visualize for Sofia. Similarly, you might find that "bulge area" or "bowl go Rio" is easier to visualize for Bulgaria.

Also, the substitute word does not need to exactly match the sound of the original word. What we are doing here is creating mental hooks to remind us of the information we have studied and want to be able to remember.

Connecting the images. Substitute words in hand (bull + Gary = Bulgaria; sofa = Sofia), I now simply need to merge them into a memorable mental image. The sillier the image, the better, since the brain most easily remembers images that are unusual.

I decide that Gary the Bull has sat down on the sofa in his living room to relax after a hard day working in the field. Notice, I've also included the silly cap on his head - to remind myself that Sofia is the capital of Bulgaria.

I review this image mentally a few times to set it in memory. Suppose that some time in the future (on an exam, for instance), I'm presented with the question, "What is the capital of Bulgaria?" If I cant' recall, I first think about the sound of the word Bulgaria.

If I clearly imagined my image and practiced it well, the thought "Bull Gary" will pop into my mind. What about Bull Gary? Oh, yes - he's lounging on his sofa. Aha - Sofia!

TIP: If you have trouble seeing images in your mind's eye, try sketching the images on paper. I refer to this as memory cartooning.

Over time, the silly images actually fade away. The time you spent creating and reviewing them has moved the information from short-term memory to long-term memory. It is now a part of your permanent body of knowledge. Mission accomplished!

Why Memory Systems Are Effective

Our minds retain a lot more information than we are able to recall at any given time. The problem is often simply getting at the information.

How many times have you forgotten an answer during an exam only to remember it later when the test was over? The information was in your brain - you just couldn't "grab" it at the time you needed it.

The visualization part of the memory systems creates a cue for remembering the information. It acts as a mental hook you can grab onto to pull the information out of your memory and into your conscious when you need it.

In addition, the very act of creating the images forces you to concentrate on the material like never before as you break down the information phonetically and visually. This also contributes to remembering the material.

And not least, having information stored in your visual memory in addition to your verbal memory (that is, in two different parts of your brain) creates two ways for you to remember it instead of just one.

Published: 12/25/2007

Last Updated: 06/11/2020

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search